Effortless

"I’d long heard laments about how babies ruined people’s lives, made them uncool. … I wanted to make it look easy."

“The chair arrives two days after the baby does.”

That’s the start of an anecdote in Ambition Monster by Jennifer Romolini. She continues:

I’d known the chair would be a problem. I’d ordered it—a pale gray “glider”... designed for “the most comfortable late-night feedings!”... because I was afraid I’d be a bad mom and I thought the chair would help me be a better one.

… I nurse the baby on the couch, I change the baby’s diaper, I apply the subby-belly button salve to the belly-button stub, I put the baby in a fresh onesies and asleep suit… then I walk to the kitchen grab our largest butcher knife, and head down the stairs. I manage to push our building’s front door open enough to slide my spongy maternity-pants-clad body out sideways and begin hacking at the thick cardboard box with the giant knife as if it is the Revenant bear. … By the time I free the expensive, unnecessary chair from the box, I’m sweating all over. … I push it away from the front of the building’s door, open the door and, with all my body’s force, move the chair inside, ripping my fresh perineum stitches as I go.

In a book full of relatable moments, I have seldom related to anything else so definitively. I have several postpartum memories like this, moments in which I insisted on doing more, sometimes much more, physically, than it was wise to do.

In the second week of my eldest’s life, after my spouse’s paltry paternity leave had ended, I took my mother and aunt to Balboa Park. I claimed I would enjoy getting out of the house, but I also felt responsible for entertaining them even as we all claimed that they were there to take care of me.

After we’d been there for a bit, I offered to buy ice cream cones while they stayed on a park bench next to the stroller and the sleeping baby inside. I walked maybe a football field away to the vendor, feeling the already unfamiliar lightness of being stroller-less, just for a few minutes. Then the ice-cream man handed me 3 top-heavy cones of soft-serve, which immediately began to melt. As I walked back toward my family, I thoughtlessly began to jog, then felt intense pain around my lower abdomen. (I’d had a c-section.) The ice cream was melting fast. I tried merely to walk quickly, but that was also a no-go. I had to slow down—way down. The more core strength I tried to marshal to balance the melting ice cream on increasingly soggy cake cones, the slower I had to walk. I ended up back at the park bench, breathing hard and sweating, with melted ice cream all over my hands.

“Napkins?” my mother said, as I crumpled onto the bench.

I didn’t rip any stitches that day, but I also didn’t learn to rest or slow down, not for several more years. And this wasn’t only after the birth of my first child, when I could explain away the tendency to “overdo it” because of my lack of experience. After the birth of my second child, I have just as many memories of pushing through the first weeks of an eyeball-burning, bone-crunching exhaustion that I swatted at listlessly as though it were an annoying fly rather than the leopard trying to eat my face off. When a leopard is trying to eat your face off, your best bet is retreat to safety, if it’s available to you. Instead, I insisted on pushing. Why?

I’m not good at resting; I can’t say I’ve met a single woman who is any good at it. But it wasn’t just that.

In the same section of Ambition Monster, Romolini writes, “I’d long heard laments about how babies ruined people’s lives, made them uncool. … I was determined to be the exception to this rule. … I wanted to make it look easy.”

Bingo. I had something to prove. I’m not like all those other postpartum moms. I’m the “exception”: I’m a cool mom.

It’s funny how universal this sentiment is among women pregnant for the first time. Each of us, in our own expectant bubble, telling ourselves that, although every other woman we know has likened having a baby to a bomb going off in the middle of their lives, I’ll be the exception. I’ll keep killing it at work/my social life/hot sex/body back/great friend/whatever.

In fact, in the years after my kids were born, I wasn’t scratching my head, saying, “Why didn’t anyone tell me this was how it was going to be?” I was gnawing on my lower lip, asking myself, “When they told me… why didn’t I listen?”

Is it possible that this inability to listen is just a personality flaw? A personality flaw that replicates from pregnant person to pregnant person, across time and space? I think there is a likelier explanation.

I cringe when I think about how sure I was that a baby upending one's life was a bad thing (rather than a natural thing), that making a whole-ass human should have done SOMETHING OTHER than upend my life.

We live within a system that benefits from each individual mother believing that her taking time to acknowledge and adjust to the huge transition that is motherhood is her “making a choice.” And not just making a choice, but making the wrong choice. The right choice is exceptionalism: I will beat the odds! And I’ll make it look easy.

****

After the Olympic women’s gymnastics competitions last month, someone I followed on Instagram lamented that today’s top gymnasts are not as “graceful” as gymnasts in previous years. I immediately unfollowed this person. Later, I thought about why I’d unfollowed them. I think it had something to do with this: I took ballet for nearly my entire childhood. Some of the other girls in my classes were gymnasts who took ballet to learn how to make their gymnastics routines look more “effortless.” This Instagrammer whom I unfollowed was arguing that this was a good thing: women gymnasts should not only knock our socks off with their athletic feats, but they should also be making it look like it’s not work. “Graceful.”

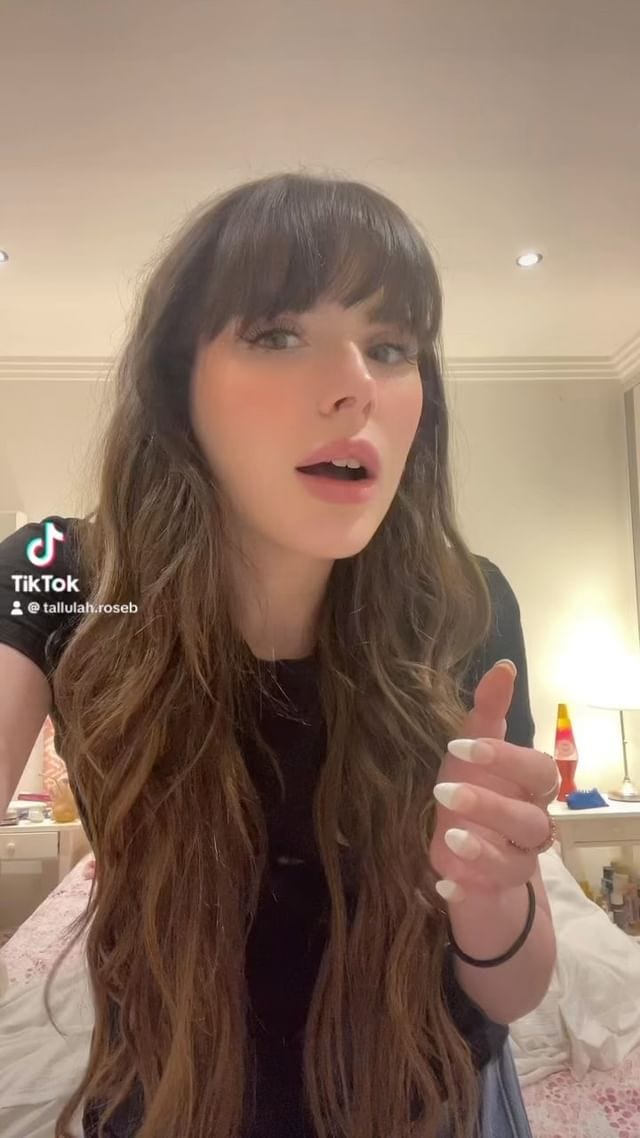

In fact, women regularly deal with an extra layer of expectation that not only will we achieve extraordinary things with our bodies, but that we will also make hard work look effortless. The expectation is that part of the work our bodies do is making it look like we’re not doing work at all. “Natural,” as Tallulah Rose skewers so brilliantly:

But who benefits when we minimize our efforts? Who says we don’t get to grrr and grunt quite loudly and publicly under the strain of hard work?

Also: what do you think? Did you experience this phenomenon of believing you’d be the “exception,” whether it was around motherhood or something else? If not, tell me what happened for you instead. Comments are open.

Maggie

PS: Different topic: The New York Times published a “100 best books of the 21st century list.” Not novels, not poetry collections, not memoirs. Just “books.” I hate how, no matter useless and arbitrary these lists are, I carefully pore over them anyway. 🤡

I’ve read 15 books on the list, if you must know. I’ve quit about 3 or 4 others. (I’ve abandoned Wolf Hall at least 3 times. Ditto Demon Copperhead.) Anyone who’s spoken to me at all in the past year knows my entire personality is now based on My Brilliant Friend being my favorite book. The list agreed. :-)

A sidebar article showed how some of the 503 authors voted. As far as I can tell, Stephen King is the only author who voted for one of his own books. Noticing this made me think of the Mediocre White Man. Of course, I would never suggest that Stephen King is a mediocre writer. (I actually haven’t read anything he’s ever written. 😈 )

But it did remind me that white men, be they mediocre or exceptional, are always the most likely of all of us to believe loudly and publicly in their own work. They’re the most likely to bring the audacity along with their talent and effort. And I suppose it’s a good lesson. If we believe in our work, nothing wrong with saying so! Just ask Stephen King.

Have a similar reaction when I hear people say women gymnasts (and figure skaters and tennis players, the list goes on) should be more "graceful." It's also like, first, you make us try to prove that we can be as good as the men, and when we do, you call us not female enough, too masculine, all power--because when i hear grace, i hear the word feminine before it.